Difference between revisions of "Directory:Jon Awbrey/Papers/Peirce's 1870 Logic Of Relatives"

Jon Awbrey (talk | contribs) |

Jon Awbrey (talk | contribs) |

||

| (295 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE:Peirce's 1870 Logic Of Relatives}} | {{DISPLAYTITLE:Peirce's 1870 Logic Of Relatives}} | ||

| − | ''' | + | '''Note.''' The MathJax parser is not rendering this page properly.<br>Until it can be fixed please see the [http://intersci.ss.uci.edu/wiki/index.php/Peirce's_1870_Logic_Of_Relatives InterSciWiki version]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Author: [[User:Jon Awbrey|Jon Awbrey]]''' | |

| − | Peirce's text employs | + | Peirce's text employs lower case letters for logical terms of general reference and upper case letters for logical terms of individual reference. General terms fall into types — absolute terms, dyadic relative terms, higher adic relative terms — and Peirce employs different typefaces to distinguish these. The following Tables indicate the typefaces that are used in the text below for Peirce's examples of general terms. |

<br> | <br> | ||

| Line 83: | Line 81: | ||

<br> | <br> | ||

| + | |||

| + | Individual terms are taken to denote individual entities falling under a general term. Peirce uses upper case Roman letters for individual terms, for example, the individual horses <math>\mathrm{H}, \mathrm{H}^{\prime}, \mathrm{H}^{\prime\prime}</math> falling under the general term <math>\mathrm{h}\!</math> for ''horse''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The path to understanding Peirce's system and its wider implications for logic can be smoothed by paraphrasing his notations in a variety of contemporary mathematical formalisms, while preserving the semantics as much as possible. Remaining faithful to Peirce's orthography while adding parallel sets of stylistic conventions will, however, demand close attention to typography-in-context. Current style sheets for mathematical texts specify italics for mathematical variables, with upper case letters for sets and lower case letters for individuals. So we need to keep an eye out for the difference between the individual <math>\mathrm{X}\!</math> of the genus <math>\mathrm{x}\!</math> and the element <math>x\!</math> of the set <math>X\!</math> as we pass between the two styles of text. | ||

| + | |||

| + | __TOC__ | ||

==Selection 1== | ==Selection 1== | ||

| Line 94: | Line 98: | ||

<p>Now logical terms are of three grand classes.</p> | <p>Now logical terms are of three grand classes.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The first embraces those whose logical form involves only the conception of quality, and which therefore represent a thing simply as | + | <p>The first embraces those whose logical form involves only the conception of quality, and which therefore represent a thing simply as “a ——”. These discriminate objects in the most rudimentary way, which does not involve any consciousness of discrimination. They regard an object as it is in itself as ''such'' (''quale''); for example, as horse, tree, or man. These are ''absolute terms''.</p> |

<p>The second class embraces terms whose logical form involves the conception of relation, and which require the addition of another term to complete the denotation. These discriminate objects with a distinct consciousness of discrimination. They regard an object as over against another, that is as relative; as father of, lover of, or servant of. These are ''simple relative terms''.</p> | <p>The second class embraces terms whose logical form involves the conception of relation, and which require the addition of another term to complete the denotation. These discriminate objects with a distinct consciousness of discrimination. They regard an object as over against another, that is as relative; as father of, lover of, or servant of. These are ''simple relative terms''.</p> | ||

| Line 100: | Line 104: | ||

<p>The third class embraces terms whose logical form involves the conception of bringing things into relation, and which require the addition of more than one term to complete the denotation. They discriminate not only with consciousness of discrimination, but with consciousness of its origin. They regard an object as medium or third between two others, that is as conjugative; as giver of —— to ——, or buyer of —— for —— from ——. These may be termed ''conjugative terms''.</p> | <p>The third class embraces terms whose logical form involves the conception of bringing things into relation, and which require the addition of more than one term to complete the denotation. They discriminate not only with consciousness of discrimination, but with consciousness of its origin. They regard an object as medium or third between two others, that is as conjugative; as giver of —— to ——, or buyer of —— for —— from ——. These may be termed ''conjugative terms''.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The conjugative term involves the conception of ''third'', the relative that of second or ''other'', the absolute term simply considers ''an'' object. No fourth class of terms exists involving the conception of ''fourth'', because when that of ''third'' is introduced, since it involves the conception of bringing objects into relation, all higher numbers are given at once, inasmuch as the conception of bringing objects into relation is independent of the number of members of the relationship. Whether this ''reason'' for the fact that there is no fourth class of terms fundamentally different from the third is satisfactory | + | <p>The conjugative term involves the conception of ''third'', the relative that of second or ''other'', the absolute term simply considers ''an'' object. No fourth class of terms exists involving the conception of ''fourth'', because when that of ''third'' is introduced, since it involves the conception of bringing objects into relation, all higher numbers are given at once, inasmuch as the conception of bringing objects into relation is independent of the number of members of the relationship. Whether this ''reason'' for the fact that there is no fourth class of terms fundamentally different from the third is satisfactory or not, the fact itself is made perfectly evident by the study of the logic of relatives.</p> |

<p>(Peirce, CP 3.63).</p> | <p>(Peirce, CP 3.63).</p> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | I am going to experiment with an interlacing commentary on Peirce's 1870 | + | I am going to experiment with an interlacing commentary on Peirce's 1870 “Logic of Relatives” paper, revisiting some critical transitions from several different angles and calling attention to a variety of puzzles, problems, and potentials that are not so often remarked or tapped. |

| − | What strikes me about the initial installment this time around is its use of a certain pattern of argument that I can recognize as invoking a | + | What strikes me about the initial installment this time around is its use of a certain pattern of argument that I can recognize as invoking a ''closure principle'', and this is a figure of reasoning that Peirce uses in three other places: his discussion of [[continuous predicates]], his definition of [[sign relations]], and in the [[pragmatic maxim]] itself. |

One might also call attention to the following two statements: | One might also call attention to the following two statements: | ||

| Line 125: | Line 129: | ||

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>I propose to use the term | + | <p>I propose to use the term “universe” to denote that class of individuals ''about'' which alone the whole discourse is understood to run. The universe, therefore, in this sense, as in Mr. De Morgan's, is different on different occasions. In this sense, moreover, discourse may run upon something which is not a subjective part of the universe; for instance, upon the qualities or collections of the individuals it contains.</p> |

| − | <p>I propose to assign to all logical terms, numbers; to an absolute term, the number of individuals it denotes; to a relative term, the average number of things so related to one individual. Thus in a universe of perfect men (''men''), the number of | + | <p>I propose to assign to all logical terms, numbers; to an absolute term, the number of individuals it denotes; to a relative term, the average number of things so related to one individual. Thus in a universe of perfect men (''men''), the number of “tooth of” would be 32. The number of a relative with two correlates would be the average number of things so related to a pair of individuals; and so on for relatives of higher numbers of correlates. I propose to denote the number of a logical term by enclosing the term in square brackets, thus <math>[t].\!</math></p> |

<p>(Peirce, CP 3.65).</p> | <p>(Peirce, CP 3.65).</p> | ||

| Line 150: | Line 154: | ||

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>I shall follow Boole in taking the sign of equality to signify identity. Thus, if <math>\mathrm{v}\!</math> denotes the Vice-President of the United States, and <math>\mathrm{p}\!</math> the President of the Senate of the United States,</p> | + | <p>I shall follow Boole in taking the sign of equality to signify identity. Thus, if <math>\mathrm{v}\!</math> denotes the Vice-President of the United States, and <math>\mathrm{p}~\!</math> the President of the Senate of the United States,</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | <math>\mathrm{v} = \mathrm{p}\!</math> | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{v} = \mathrm{p}\!</math> | ||

| Line 157: | Line 161: | ||

<p>means that every Vice-President of the United States is President of the Senate, and every President of the United States Senate is Vice-President.</p> | <p>means that every Vice-President of the United States is President of the Senate, and every President of the United States Senate is Vice-President.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The sign | + | <p>The sign “less than” is to be so taken that</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} < \mathrm{m}\!</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} < \mathrm{m}~\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>means that every Frenchman is a man, but there are men besides Frenchmen. Drobisch has used this sign in the same sense. It will follow from these significations of <math>=\!</math> and <math><\!</math> that the sign <math>-\!\!\!<\!</math> (or <math>\leqq</math>, | + | <p>means that every Frenchman is a man, but there are men besides Frenchmen. Drobisch has used this sign in the same sense. It will follow from these significations of <math>=\!</math> and <math><\!</math> that the sign <math>-\!\!\!<\!</math> (or <math>\leqq</math>, “as small as”) will mean “is”. Thus,</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} -\!\!\!< \mathrm{m}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} ~-\!\!\!< \mathrm{m}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>means | + | <p>means “every Frenchman is a man”, without saying whether there are any other men or not. So,</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{m} -\!\!\!< \mathit{l}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{m} ~-\!\!\!< \mathit{l}</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 177: | Line 181: | ||

{| width="100%" | {| width="100%" | ||

| width="25%" | | | width="25%" | | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} -\!\!\!< \mathrm{m}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} ~-\!\!\!< \mathrm{m}</math> |

| width="25%" | | | width="25%" | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <p>and</p> | | <p>and</p> | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m} -\!\!\!< \mathrm{a}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m} ~-\!\!\!< \mathrm{a}</math> |

| | | | ||

|- | |- | ||

| <p>we can infer that</p> | | <p>we can infer that</p> | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} -\!\!\!< \mathrm{a}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{f} ~-\!\!\!< \mathrm{a}</math> |

| | | | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 192: | Line 196: | ||

<p>that is, from every Frenchman being a man and every man being an animal, that every Frenchman is an animal.</p> | <p>that is, from every Frenchman being a man and every man being an animal, that every Frenchman is an animal.</p> | ||

| − | <p>But not only do the significations of <math>=\!</math> and <math><\!</math> here adopted fulfill all absolute requirements, but they have the supererogatory virtue of being very nearly the same as the common significations. Equality is, in fact, nothing but the identity of two numbers; numbers that are equal are those which are predicable of the same collections, just as terms that are identical are those which are predicable of the same classes. So, to write <math>5 < 7\!</math> is to say that <math>5\!</math> is part of <math>7\!</math>, just as to write <math>\mathrm{f} < \mathrm{m}\!</math> is to say that Frenchmen are part of men. Indeed, if <math>\mathrm{f} < \mathrm{m}\!</math>, then the number of Frenchmen is less than the number of men, and if <math>\mathrm{v} = \mathrm{p}\!</math>, then the number of Vice-Presidents is equal to the number of Presidents of the Senate; so that the numbers may always be substituted for the terms themselves, in case no signs of operation occur in the equations or inequalities.</p> | + | <p>But not only do the significations of <math>=\!</math> and <math><\!</math> here adopted fulfill all absolute requirements, but they have the supererogatory virtue of being very nearly the same as the common significations. Equality is, in fact, nothing but the identity of two numbers; numbers that are equal are those which are predicable of the same collections, just as terms that are identical are those which are predicable of the same classes. So, to write <math>5 < 7\!</math> is to say that <math>5\!</math> is part of <math>7\!</math>, just as to write <math>\mathrm{f} < \mathrm{m}~\!</math> is to say that Frenchmen are part of men. Indeed, if <math>\mathrm{f} < \mathrm{m}~\!</math>, then the number of Frenchmen is less than the number of men, and if <math>\mathrm{v} = \mathrm{p}\!</math>, then the number of Vice-Presidents is equal to the number of Presidents of the Senate; so that the numbers may always be substituted for the terms themselves, in case no signs of operation occur in the equations or inequalities.</p> |

<p>(Peirce, CP 3.66).</p> | <p>(Peirce, CP 3.66).</p> | ||

| Line 199: | Line 203: | ||

The quantifier mapping from terms to their numbers that Peirce signifies by means of the square bracket notation <math>[t]\!</math> has one of its principal uses in providing a basis for the computation of frequencies, probabilities, and all of the other statistical measures that can be constructed from these, and thus in affording what may be called a ''principle of correspondence'' between probability theory and its limiting case in the forms of logic. | The quantifier mapping from terms to their numbers that Peirce signifies by means of the square bracket notation <math>[t]\!</math> has one of its principal uses in providing a basis for the computation of frequencies, probabilities, and all of the other statistical measures that can be constructed from these, and thus in affording what may be called a ''principle of correspondence'' between probability theory and its limiting case in the forms of logic. | ||

| − | This brings us once again to the relativity of contingency and necessity, as one way of approaching necessity is through the avenue of probability, describing necessity as a probability of 1, but the whole apparatus of probability theory only figures in if it is cast against the backdrop of probability space axioms, the reference class of distributions, and the sample space that we cannot help but to | + | This brings us once again to the relativity of contingency and necessity, as one way of approaching necessity is through the avenue of probability, describing necessity as a probability of 1, but the whole apparatus of probability theory only figures in if it is cast against the backdrop of probability space axioms, the reference class of distributions, and the sample space that we cannot help but to abduce upon the scene of observations. Aye, there's the snake eyes. And with them we can see that there is always an irreducible quantum of facticity to all our necessities. More plainly spoken, it takes a fairly complex conceptual infrastructure just to begin speaking of probabilities, and this setting can only be set up by means of abductive, fallible, hypothetical, and inherently risky mental acts. |

| − | Pragmatic thinking is the logic of abduction, which is just another way of saying that it addresses the question: | + | Pragmatic thinking is the logic of abduction, which is just another way of saying that it addresses the question: “What may be hoped?” We have to face the possibility that it may be just as impossible to speak of “absolute identity” with any hope of making practical philosophical sense as it is to speak of “absolute simultaneity” with any hope of making operational physical sense. |

==Selection 4== | ==Selection 4== | ||

| Line 218: | Line 222: | ||

<p>Thus</p> | <p>Thus</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m} + \mathrm{w}\!</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m} + \mathrm{w}~\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 256: | Line 260: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | A wealth of issues | + | A wealth of issues arises here that I hope to take up in depth at a later point, but for the moment I shall be able to mention only the barest sample of them in passing. |

| − | The two papers that precede this one in CP 3 are Peirce's papers of March and September 1867 in the 'Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences', titled | + | The two papers that precede this one in CP 3 are Peirce's papers of March and September 1867 in the ''Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences'', titled “On an Improvement in Boole's Calculus of Logic” and “Upon the Logic of Mathematics”, respectively. Among other things, these two papers provide us with further clues about the motivating considerations that brought Peirce to introduce the “number of a term” function, signified here by square brackets. I have already quoted from the “Logic of Mathematics” paper in a related connection. Here are the links to those excerpts: |

| − | : | + | <dl style="margin-left:30px;"> |

| − | : | + | <dt>Limited Mark Universes |

| + | <dd>[http://web.archive.org/web/20140429004255/http://suo.ieee.org/ontology/msg04349.html (1)] | ||

| + | <dd>[http://web.archive.org/web/20140429004359/http://suo.ieee.org/ontology/msg04350.html (2)] | ||

| + | <dd>[http://web.archive.org/web/20140429004130/http://suo.ieee.org/ontology/msg04351.html (3)] | ||

| + | </dl> | ||

| − | In setting up a correspondence between | + | In setting up a correspondence between “letters” and “numbers”, Peirce constructs a structure-preserving map from a logical domain to a numerical domain. That he does this deliberately is evidenced by the care that he takes with the conditions under which the chosen aspects of structure are preserved, along with his recognition of the critical fact that zeroes are preserved by the mapping. |

| − | + | Incidentally, Peirce appears to have an inkling of the problems that would later be caused by using the plus sign for inclusive disjunction, but his advice was overridden by the dialects of applied logic that developed in various communities, retarding the exchange of information among engineering, mathematical, and philosophical specialties all throughout the subsequent century. | |

==Selection 5== | ==Selection 5== | ||

| Line 273: | Line 281: | ||

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>I shall adopt for the conception of multiplication ''the application of a relation'', in such a way that, for example, <math>\mathit{l}\mathrm{w}\!</math> shall denote whatever is lover of a woman. This notation is the same as that used by Mr. De Morgan, although he | + | <p>I shall adopt for the conception of multiplication ''the application of a relation'', in such a way that, for example, <math>\mathit{l}\mathrm{w}~\!</math> shall denote whatever is lover of a woman. This notation is the same as that used by Mr. De Morgan, although he appears not to have had multiplication in his mind.</p> |

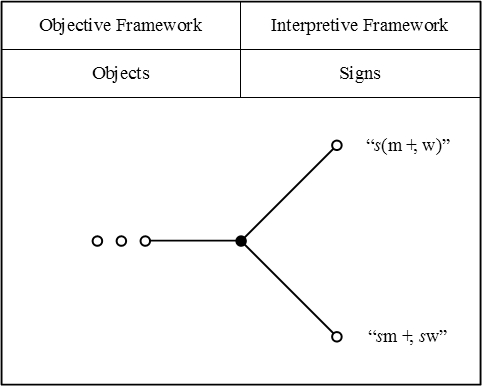

<p><math>\mathit{s}(\mathrm{m} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{w})</math> will, then, denote whatever is servant of anything of the class composed of men and women taken together. So that:</p> | <p><math>\mathit{s}(\mathrm{m} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{w})</math> will, then, denote whatever is servant of anything of the class composed of men and women taken together. So that:</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{s}(\mathrm{m} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{w}) ~=~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{m} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{s}(\mathrm{m} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{w}) ~=~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{m} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{w}.</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

<p><math>(\mathit{l} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s})\mathrm{w}</math> will denote whatever is lover or servant to a woman, and:</p> | <p><math>(\mathit{l} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s})\mathrm{w}</math> will denote whatever is lover or servant to a woman, and:</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>(\mathit{l} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s})\mathrm{w} ~=~ \mathit{l}\mathrm{w} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>(\mathit{l} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s})\mathrm{w} ~=~ \mathit{l}\mathrm{w} ~+\!\!,~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{w}.</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

<p><math>(\mathit{s}\mathit{l})\mathrm{w}\!</math> will denote whatever stands to a woman in the relation of servant of a lover, and:</p> | <p><math>(\mathit{s}\mathit{l})\mathrm{w}\!</math> will denote whatever stands to a woman in the relation of servant of a lover, and:</p> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>(\mathit{s}\mathit{l})\mathrm{w} ~=~ \mathit{s}(\mathit{l}\mathrm{w})</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>(\mathit{s}\mathit{l})\mathrm{w} ~=~ \mathit{s}(\mathit{l}\mathrm{w}).</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

<p>Thus all the absolute conditions of multiplication are satisfied.</p> | <p>Thus all the absolute conditions of multiplication are satisfied.</p> | ||

| − | <p>The term | + | <p>The term “identical with ——” is a unity for this multiplication. That is to say, if we denote “identical with ——” by <math>\mathit{1}\!</math> we have:</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| − | | align="center" | <math>x \mathit{1} ~=~ x</math> | + | | align="center" | <math>x \mathit{1} ~=~ x ~ ,</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 302: | Line 310: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Peirce in 1870 is five years down the road from the Peirce of 1865–1866 who lectured extensively on the role of sign relations in the logic of scientific inquiry, articulating their involvement in the three types of inference, and inventing the concept of | + | Peirce in 1870 is five years down the road from the Peirce of 1865–1866 who lectured extensively on the role of sign relations in the logic of scientific inquiry, articulating their involvement in the three types of inference, and inventing the concept of “information” to explain what it is that signs convey in the process. By this time, then, the semiotic or sign relational approach to logic is so implicit in his way of working that he does not always take the trouble to point out its distinctive features at each and every turn. So let's take a moment to draw out a few of these characters. |

| − | [[Sign | + | [[Sign relations]], like any brand of non-trivial [[3-adic relations]], can become overwhelming to think about once the cardinality of the object, sign, and interpretant domains or the complexity of the relation itself ascends beyond the simplest examples. Furthermore, most of the strategies that we would normally use to control the complexity, like neglecting one of the domains, in effect, projecting the 3-adic sign relation onto one of its 2-adic faces, or focusing on a single ordered triple of the form <math>(o, s, i)\!</math> at a time, can result in our receiving a distorted impression of the sign relation's true nature and structure. |

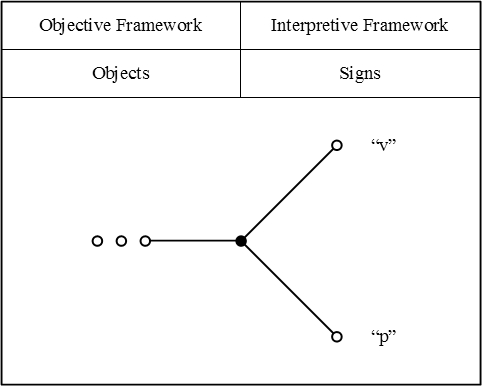

I find that it helps me to draw, or at least to imagine drawing, diagrams of the following form, where I can keep tabs on what's an object, what's a sign, and what's an interpretant sign, for a selected set of sign-relational triples. | I find that it helps me to draw, or at least to imagine drawing, diagrams of the following form, where I can keep tabs on what's an object, what's a sign, and what's an interpretant sign, for a selected set of sign-relational triples. | ||

| − | Here is how I would picture Peirce's example of equivalent terms, <math>\mathrm{v} = \mathrm{p}\!</math> | + | Here is how I would picture Peirce's example of equivalent terms, <math>\mathrm{v} = \mathrm{p},\!</math> where <math>{}^{\backprime\backprime} \mathrm{v} {}^{\prime\prime}\!</math> denotes the Vice-President of the United States, and <math>{}^{\backprime\backprime} \mathrm{p} {}^{\prime\prime}\!</math> denotes the President of the Senate of the United States. |

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" border="0" cellspacing="10" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 1.jpg]] | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | height="20px" valign="top" | <math>\text{Figure 1}~\!</math> | |

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Depending on whether we interpret the terms <math>^{\backprime\backprime} \mathrm{v} ^{\prime\prime}</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime} \mathrm{p} ^{\prime\prime}</math> as applying to persons who hold these offices at one particular time or as applying to all those persons who have held these offices over an extended period of history, their denotations may be either singular of plural, respectively. | + | Depending on whether we interpret the terms <math>{}^{\backprime\backprime} \mathrm{v} {}^{\prime\prime}\!</math> and <math>{}^{\backprime\backprime} \mathrm{p} {}^{\prime\prime}\!</math> as applying to persons who hold these offices at one particular time or as applying to all those persons who have held these offices over an extended period of history, their denotations may be either singular of plural, respectively. |

| − | As a shortcut technique for indicating general denotations or plural referents, I will use the ''elliptic convention'' that represents these by means of figures like | + | As a shortcut technique for indicating general denotations or plural referents, I will use the ''elliptic convention'' that represents these by means of figures like “o o o” or “o … o”, placed at the object ends of sign relational triads. |

For a more complex example, here is how I would picture Peirce's example of an equivalence between terms that comes about by applying one of the distributive laws, for relative multiplication over absolute summation. | For a more complex example, here is how I would picture Peirce's example of an equivalence between terms that comes about by applying one of the distributive laws, for relative multiplication over absolute summation. | ||

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" border="0" cellspacing="10" style="text-align:center; width:100%" |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 2.jpg]] | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | height="20px" valign="top" | <math>\text{Figure 2}\!</math> | |

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | </ | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 370: | Line 344: | ||

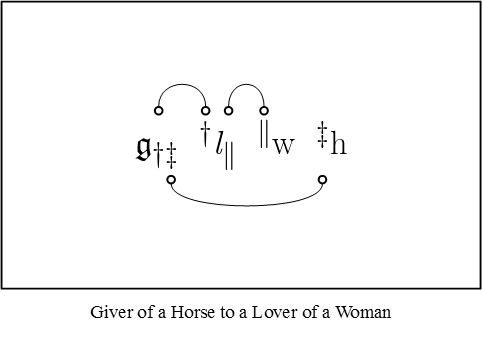

<p>A conjugative term like ''giver'' naturally requires two correlates, one denoting the thing given, the other the recipient of the gift.</p> | <p>A conjugative term like ''giver'' naturally requires two correlates, one denoting the thing given, the other the recipient of the gift.</p> | ||

| − | <p>We must be able to distinguish, in our notation, the giver of <math>\mathrm{A}\!</math> to <math>\mathrm{B}\!</math> from the giver to <math>\mathrm{A}\!</math> of <math>\mathrm{B}\!</math>, and, therefore, I suppose the signification of the letter equivalent to such a relative to distinguish the correlates as first, second, third, etc., so that | + | <p>We must be able to distinguish, in our notation, the giver of <math>\mathrm{A}\!</math> to <math>\mathrm{B}\!</math> from the giver to <math>\mathrm{A}\!</math> of <math>\mathrm{B}\!</math>, and, therefore, I suppose the signification of the letter equivalent to such a relative to distinguish the correlates as first, second, third, etc., so that “giver of —— to ——” and “giver to —— of ——” will be expressed by different letters.</p> |

<p>Let <math>\mathfrak{g}</math> denote the latter of these conjugative terms. Then, the correlates or multiplicands of this multiplier cannot all stand directly after it, as is usual in multiplication, but may be ranged after it in regular order, so that:</p> | <p>Let <math>\mathfrak{g}</math> denote the latter of these conjugative terms. Then, the correlates or multiplicands of this multiplier cannot all stand directly after it, as is usual in multiplication, but may be ranged after it in regular order, so that:</p> | ||

| Line 407: | Line 381: | ||

<p>we abandon the associative principle of multiplication.</p> | <p>we abandon the associative principle of multiplication.</p> | ||

| − | <p>A little reflection will show that the associative principle must in some form or other be abandoned at this point. But while this principle is sometimes falsified, it oftener holds, and a notation must be adopted which will show of itself when it holds. We already see that we cannot express multiplication by writing the multiplicand directly after the multiplier; let us then affix subjacent numbers after letters to show where their correlates are to be found. The first number shall denote how many factors must be counted from left to right to reach the first correlate, the second how many 'more' must be counted to reach the second, and so on.</p> | + | <p>A little reflection will show that the associative principle must in some form or other be abandoned at this point. But while this principle is sometimes falsified, it oftener holds, and a notation must be adopted which will show of itself when it holds. We already see that we cannot express multiplication by writing the multiplicand directly after the multiplier; let us then affix subjacent numbers after letters to show where their correlates are to be found. The first number shall denote how many factors must be counted from left to right to reach the first correlate, the second how many ''more'' must be counted to reach the second, and so on.</p> |

<p>Then, the giver of a horse to a lover of a woman may be written:</p> | <p>Then, the giver of a horse to a lover of a woman may be written:</p> | ||

| Line 442: | Line 416: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>This enables us to retain our former expressions <math>\mathit{l}\mathrm{w}\!</math>, <math>\mathfrak{g}\mathit{o}\mathrm{h}</math>, etc.</p> | + | <p>This enables us to retain our former expressions <math>\mathit{l}\mathrm{w}~\!</math>, <math>\mathfrak{g}\mathit{o}\mathrm{h}</math>, etc.</p> |

<p>(Peirce, CP 3.69–70).</p> | <p>(Peirce, CP 3.69–70).</p> | ||

| Line 455: | Line 429: | ||

Let us look at a few simple examples of generating functions, much as I encountered them during my own first adventures in the Fair Land Of Combinatoria. | Let us look at a few simple examples of generating functions, much as I encountered them during my own first adventures in the Fair Land Of Combinatoria. | ||

| − | Suppose that we are given a set of three elements, say, <math>\{ a, b, c \}\!</math> | + | Suppose that we are given a set of three elements, say, <math>\{ a, b, c \},\!</math> and we are asked to find all the ways of choosing a subset from this collection. |

We can represent this problem setup as the problem of computing the following product: | We can represent this problem setup as the problem of computing the following product: | ||

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| − | | <math>(1 + a)(1 + b)(1 + c)\!</math> | + | | <math>(1 + a)(1 + b)(1 + c).\!</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| − | The factor <math>(1 + a)\!</math> represents the option that we have, in choosing a subset of <math>\{ a, b, c \}\!</math> | + | The factor <math>(1 + a)\!</math> represents the option that we have, in choosing a subset of <math>\{ a, b, c \},\!</math> to leave the element <math>a\!</math> out (signified by the <math>1\!</math>), or else to include it (signified by the <math>a\!</math>), and likewise for the other elements <math>b\!</math> and <math>c\!</math> in their turns. |

Probably on account of all those years I flippered away playing the oldtime pinball machines, I tend to imagine a product like this being displayed in a vertical array: | Probably on account of all those years I flippered away playing the oldtime pinball machines, I tend to imagine a product like this being displayed in a vertical array: | ||

| Line 482: | Line 456: | ||

So a trajectory of the ball where it hits the <math>a\!</math> bumper on the 1st level, hits the <math>1\!</math> bumper on the 2nd level, hits the <math>c\!</math> bumper on the 3rd level, and then exits the board, represents a single term in the desired product and corresponds to the subset <math>\{ a, c \}.\!</math> | So a trajectory of the ball where it hits the <math>a\!</math> bumper on the 1st level, hits the <math>1\!</math> bumper on the 2nd level, hits the <math>c\!</math> bumper on the 3rd level, and then exits the board, represents a single term in the desired product and corresponds to the subset <math>\{ a, c \}.\!</math> | ||

| − | Multiplying out the product <math>(1 + a)(1 + b)(1 + c)\!</math> | + | Multiplying out the product <math>(1 + a)(1 + b)(1 + c),\!</math> one obtains: |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | <math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | ||

| − | 1 & + & a & + & b & + & c & + & ab & + & ac & + & bc & + & abc | + | 1 & + & a & + & b & + & c & + & ab & + & ac & + & bc & + & abc. |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 496: | Line 470: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | \varnothing, & \{ a \}, & \{ b \}, & \{ c \}, & \{ a, b \}, & \{ a, c \}, & \{ b, c \}, & \{ a, b, c \} | + | \varnothing, & \{ a \}, & \{ b \}, & \{ c \}, & \{ a, b \}, & \{ a, c \}, & \{ b, c \}, & \{ a, b, c \}. |

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 524: | Line 498: | ||

It is clear from our last excerpt that Peirce is already on the verge of a graphical syntax for the logic of relatives. Indeed, it seems likely that he had already reached this point in his own thinking. | It is clear from our last excerpt that Peirce is already on the verge of a graphical syntax for the logic of relatives. Indeed, it seems likely that he had already reached this point in his own thinking. | ||

| − | For instance, it seems quite impossible to read his last variation on the theme of a | + | For instance, it seems quite impossible to read his last variation on the theme of a “giver of a horse to a lover of a woman” without drawing lines of identity to connect up the corresponding marks of reference, like this: |

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" |

| − | | | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 3.jpg]] || (3) |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 552: | Line 512: | ||

<p>Thus far, we have considered the multiplication of relative terms only. Since our conception of multiplication is the application of a relation, we can only multiply absolute terms by considering them as relatives.</p> | <p>Thus far, we have considered the multiplication of relative terms only. Since our conception of multiplication is the application of a relation, we can only multiply absolute terms by considering them as relatives.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Now the absolute term | + | <p>Now the absolute term “man” is really exactly equivalent to the relative term “man that is ——”, and so with any other. I shall write a comma after any absolute term to show that it is so regarded as a relative term.</p> |

| − | <p>Then | + | <p>Then “man that is black” will be written:</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m},\!\mathrm{b}\!</math> | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m},\!\mathrm{b}\!</math> | ||

| Line 595: | Line 555: | ||

<p>If, therefore, <math>\mathit{l},\!,\!\mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> is not the same as <math>\mathit{l},\!\mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> (as it plainly is not, because the latter means a lover and servant of a woman, and the former a lover of and servant of and same as a woman), this is simply because the writing of the comma alters the arrangement of the correlates.</p> | <p>If, therefore, <math>\mathit{l},\!,\!\mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> is not the same as <math>\mathit{l},\!\mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> (as it plainly is not, because the latter means a lover and servant of a woman, and the former a lover of and servant of and same as a woman), this is simply because the writing of the comma alters the arrangement of the correlates.</p> | ||

| − | <p>And if we are to suppose that absolute terms are multipliers at all (as mathematical generality demands that we should}, we must regard every term as being a relative requiring an infinite number of correlates to its virtual infinite series | + | <p>And if we are to suppose that absolute terms are multipliers at all (as mathematical generality demands that we should}, we must regard every term as being a relative requiring an infinite number of correlates to its virtual infinite series “that is —— and is —— and is —— etc.”</p> |

<p>Now a relative formed by a comma of course receives its subjacent numbers like any relative, but the question is, What are to be the implied subjacent numbers for these implied correlates?</p> | <p>Now a relative formed by a comma of course receives its subjacent numbers like any relative, but the question is, What are to be the implied subjacent numbers for these implied correlates?</p> | ||

| Line 606: | Line 566: | ||

<p>A subjacent number may therefore be as great as we please.</p> | <p>A subjacent number may therefore be as great as we please.</p> | ||

| − | <p>But all these ''ones'' denote the same identical individual denoted by <math>\mathrm{w}\!</math>; what then can be the subjacent numbers to be applied to <math>\mathit{s}\!</math>, for instance, on account of its infinite | + | <p>But all these ''ones'' denote the same identical individual denoted by <math>\mathrm{w}\!</math>; what then can be the subjacent numbers to be applied to <math>\mathit{s}\!</math>, for instance, on account of its infinite “''that is''”'s? What numbers can separate it from being identical with <math>\mathrm{w}\!</math>? There are only two. The first is ''zero'', which plainly neutralizes a comma completely, since</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | <math>\mathit{s},_0\!\mathrm{w} ~=~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{s},_0\!\mathrm{w} ~=~ \mathit{s}\mathrm{w}</math> | ||

| Line 622: | Line 582: | ||

<p>Any term, then, is properly to be regarded as having an infinite number of commas, all or some of which are neutralized by zeros.</p> | <p>Any term, then, is properly to be regarded as having an infinite number of commas, all or some of which are neutralized by zeros.</p> | ||

| − | <p> | + | <p>“Something” may then be expressed by:</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | <math>\mathit{1}_\infty\!</math> | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{1}_\infty\!</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>I shall for brevity frequently express this by an antique figure one <math>(\mathfrak{1}).</math> | + | <p>I shall for brevity frequently express this by an antique figure one <math>(\mathfrak{1}).</math></p> |

| − | <p> | + | <p>“Anything” by:</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | <math>\mathit{1}_0\!</math> | | align="center" | <math>\mathit{1}_0\!</math> | ||

| Line 641: | Line 601: | ||

===Commentary Note 8.1=== | ===Commentary Note 8.1=== | ||

| − | To my way of thinking, CP 3.73 is one of the most remarkable passages in the history of logic. In this first pass over its deeper contents I won't be able to accord it much more than a superficial dusting off. | + | To my way of thinking, CP 3.73 is one of the most remarkable passages in the history of logic. In this first pass over its deeper contents I won't be able to accord it much more than a superficial dusting off. |

Let us imagine a concrete example that will serve in developing the uses of Peirce's notation. Entertain a discourse whose universe <math>X\!</math> will remind us a little of the cast of characters in Shakespeare's ''Othello''. | Let us imagine a concrete example that will serve in developing the uses of Peirce's notation. Entertain a discourse whose universe <math>X\!</math> will remind us a little of the cast of characters in Shakespeare's ''Othello''. | ||

| Line 649: | Line 609: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | The universe <math>X\!</math> is | + | The universe <math>X\!</math> is “that class of individuals ''about'' which alone the whole discourse is understood to run” but its marking out for special recognition as a universe of discourse in no way rules out the possibility that “discourse may run upon something which is not a subjective part of the universe; for instance, upon the qualities or collections of the individuals it contains” (CP 3.65). |

| − | In order to provide ourselves with the convenience of abbreviated terms, while preserving Peirce's conventions about capitalization, we may use the alternate names <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\mathrm{u}^{\prime\prime}</math> for the universe <math>X\!</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\mathrm{Jeste}^{\prime\prime}</math> for the character <math>\mathrm{Clown}.\!</math> This permits the above description of the universe of discourse to be rewritten in the following fashion: | + | In order to provide ourselves with the convenience of abbreviated terms, while preserving Peirce's conventions about capitalization, we may use the alternate names <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\mathrm{u}^{\prime\prime}</math> for the universe <math>X\!</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\mathrm{Jeste}^{\prime\prime}</math> for the character <math>\mathrm{Clown}.~\!</math> This permits the above description of the universe of discourse to be rewritten in the following fashion: |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| Line 662: | Line 622: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | <math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | ||

| − | 1 | + | \mathbf{1} |

& = & \mathrm{B} | & = & \mathrm{B} | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{C} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{C} | ||

| Line 732: | Line 692: | ||

===Commentary Note 8.2=== | ===Commentary Note 8.2=== | ||

| − | I | + | I continue with my commentary on CP 3.73, developing the ''Othello'' example as a way of illustrating Peirce's concepts. |

In the development of the story so far, we have a universe of discourse that can be characterized by means of the following system of equations: | In the development of the story so far, we have a universe of discourse that can be characterized by means of the following system of equations: | ||

| Line 739: | Line 699: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | <math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | ||

| − | 1 | + | \mathbf{1} |

| − | & = & | + | & = & \mathrm{B} |

| − | \mathrm{B} | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{C} |

| − | & +\!\!, & | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} |

| − | \mathrm{C} | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{E} |

| − | & +\!\!, & | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{I} |

| − | \mathrm{D} | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{J} |

| − | & +\!\!, & | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{O} |

| − | \mathrm{E} | ||

| − | & +\!\!, & | ||

| − | \mathrm{I} | ||

| − | & +\!\!, & | ||

| − | \mathrm{J} | ||

| − | & +\!\!, & | ||

| − | \mathrm{O} | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

\mathrm{b} | \mathrm{b} | ||

| − | & = & | + | & = & \mathrm{O} |

| − | \mathrm{O} | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

\mathrm{m} | \mathrm{m} | ||

| − | & = & | + | & = & \mathrm{C} |

| − | \mathrm{C} | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{I} |

| − | & +\!\!, & | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{J} |

| − | \mathrm{I} | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{O} |

| − | & +\!\!, & | + | \\[6pt] |

| − | \mathrm{J} | ||

| − | & +\!\!, & | ||

| − | \mathrm{O} | ||

| − | \\[6pt] | ||

\mathrm{w} | \mathrm{w} | ||

| − | & = & | + | & = & \mathrm{B} |

| − | \mathrm{B} | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} |

| − | & +\!\!, & | + | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{E} |

| − | \mathrm{D} | ||

| − | & +\!\!, & | ||

| − | \mathrm{E} | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 786: | Line 731: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{l} | <math>\begin{array}{l} | ||

| − | ^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime} | + | ^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

| − | ^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime} | + | ^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

| − | ^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{to}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{from}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime} | + | ^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{to}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{from}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime} |

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 800: | Line 745: | ||

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>The relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math><p> | + | <p>The relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> |

<p>can be reached by removing the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Emilia}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | <p>can be reached by removing the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Emilia}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | ||

| Line 806: | Line 751: | ||

<p>from the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of Emilia}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | <p>from the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of Emilia}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | ||

| − | <p><math>\ | + | <p><math>\text{Iago}</math> is a lover of <math>\text{Emilia},</math> so the relate-correlate pair <math>\mathrm{I}:\mathrm{E}</math></p> |

| − | <p>lies in the 2-adic relation associated with the relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | + | <p>lies in the 2-adic relation associated with the relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>The relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | + | <p>The relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> |

<p>can be reached by removing the absolute terms <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Othello}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Desdemona}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | <p>can be reached by removing the absolute terms <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Othello}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Desdemona}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | ||

| Line 817: | Line 762: | ||

<p>from the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to Othello of Desdemona}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | <p>from the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to Othello of Desdemona}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | ||

| − | <p><math>\ | + | <p><math>\text{Iago}</math> is a betrayer to <math>\text{Othello}</math> of <math>\text{Desdemona},</math> so the relate-correlate-correlate triple <math>\mathrm{I}:\mathrm{O}:\mathrm{D}</math></p> |

| − | <p>lies in the 3-adic relation assciated with the relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | + | <p>lies in the 3-adic relation assciated with the relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{betrayer to}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.\!</math></p> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>The relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{to}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{from}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | + | <p>The relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{to}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{from}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> |

<p>can be reached by removing the absolute terms <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Othello}\, ^{\prime\prime},</math> <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Iago}\, ^{\prime\prime},</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Cassio}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | <p>can be reached by removing the absolute terms <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Othello}\, ^{\prime\prime},</math> <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Iago}\, ^{\prime\prime},</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{Cassio}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math></p> | ||

| Line 828: | Line 773: | ||

<p>from the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of Othello to Iago from Cassio}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | <p>from the absolute term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of Othello to Iago from Cassio}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | ||

| − | <p><math>\ | + | <p><math>\text{Iago}</math> is a winner over of <math>\text{Othello}</math> to <math>\text{Iago}</math> from <math>\text{Cassio},\!</math> so the elementary relative term <math>\mathrm{I}:\mathrm{O}:\mathrm{I}:\mathrm{C}</math></p> |

| − | <p>lies in the 4-adic relation associated with the relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{to}\, \underline{~~~~}\, \text{from}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> | + | <p>lies in the 4-adic relation associated with the relative term <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{winner over of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{to}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, \text{from}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math></p> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 845: | Line 790: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Returning to the Othello example, let us take up the 2-adic relatives <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{servant of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math> | + | Returning to the Othello example, let us take up the 2-adic relatives <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math> and <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{servant of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math> |

| − | Ignoring the many splendored nuances appurtenant to the idea of love, we may regard the relative term <math>\mathit{l}\!</math> for <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math> to be given by the following equation: | + | Ignoring the many splendored nuances appurtenant to the idea of love, we may regard the relative term <math>\mathit{l}\!</math> for <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{lover of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}</math> to be given by the following equation: |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| Line 868: | Line 813: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | If for no better reason than to make the example more interesting, let us put aside all distinctions of rank and fealty, collapsing the motley crews of attendant, servant, subordinate, and so on, under the heading of a single service, denoted by the relative term <math>\mathit{s}\!</math> for <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{servant of}\, \underline{~~~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math> The terms of this service are: | + | If for no better reason than to make the example more interesting, let us put aside all distinctions of rank and fealty, collapsing the motley crews of attendant, servant, subordinate, and so on, under the heading of a single service, denoted by the relative term <math>\mathit{s}\!</math> for <math>^{\backprime\backprime}\, \text{servant of}\, \underline{~~ ~~}\, ^{\prime\prime}.</math> The terms of this service are: |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| Line 902: | Line 847: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | <math>\begin{array}{*{15}{c}} | ||

| − | 1 | + | \mathbf{1} |

& = & \mathrm{B} | & = & \mathrm{B} | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{C} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{C} | ||

| Line 924: | Line 869: | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{E} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{E} | ||

| − | \end{array}</math> | + | \end{array}\!</math> |

|} | |} | ||

| Line 954: | Line 899: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

| − | \mathit{l}1 | + | \mathit{l}\mathbf{1} |

& = & | & = & | ||

\text{lover of anything} | \text{lover of anything} | ||

| Line 1,041: | Line 986: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

| − | \mathit{s}1 | + | \mathit{s}\mathbf{1} |

& = & | & = & | ||

\text{servant of anything} | \text{servant of anything} | ||

| Line 1,127: | Line 1,072: | ||

\mathit{l}\mathit{s} | \mathit{l}\mathit{s} | ||

& = & | & = & | ||

| − | \text{lover of a servant of}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | \text{lover of a servant of}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & | & = & | ||

| Line 1,148: | Line 1,093: | ||

\mathit{s}\mathit{l} | \mathit{s}\mathit{l} | ||

& = & | & = & | ||

| − | \text{servant of a lover of}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | \text{servant of a lover of}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & | & = & | ||

| Line 1,164: | Line 1,109: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Among other things, one observes that the relative terms <math>\mathit{l}\!</math> and <math>\mathit{s}\!</math> do not commute, that is, <math>\mathit{l}\mathit{s}\!</math> is not equal to <math>\mathit{s}\mathit{l}.\!</math> | + | Among other things, one observes that the relative terms <math>\mathit{l}\!</math> and <math>\mathit{s}\!</math> do not commute, that is, <math>\mathit{l}\mathit{s}\!</math> is not equal to <math>\mathit{s}\mathit{l}.~\!</math> |

===Commentary Note 8.5=== | ===Commentary Note 8.5=== | ||

| Line 1,247: | Line 1,192: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Here are the 2-adic relative terms again, followed by their representation as coefficient matrices, in this case bordered by row and column labels to remind us what the coefficient values are meant | + | Here are the 2-adic relative terms again, followed by their representation as coefficient matrices, in this case bordered by row and column labels to remind us what the coefficient values are meant to signify. |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| Line 1,478: | Line 1,423: | ||

\begin{bmatrix} | \begin{bmatrix} | ||

0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 | 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 1 | ||

| − | \end{bmatrix} | + | \end{bmatrix}\! |

</math> | </math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 1,585: | Line 1,530: | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

\mathit{s}\mathrm{w} & = & \text{servant of a woman} & = | \mathit{s}\mathrm{w} & = & \text{servant of a woman} & = | ||

| − | \end{matrix}</math> | + | \end{matrix}\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| | | | ||

| Line 1,617: | Line 1,562: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | \mathit{l}\mathit{s} & = & \ | + | \mathit{l}\mathit{s} & = & \text{lover of a servant of ---} & = |

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 1,674: | Line 1,619: | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{matrix} | <math>\begin{matrix} | ||

| − | \mathit{s}\mathit{l} & = & \ | + | \mathit{s}\mathit{l} & = & \text{servant of a lover of ---} & = |

\end{matrix}</math> | \end{matrix}</math> | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 1,736: | Line 1,681: | ||

<p>Thus far, we have considered the multiplication of relative terms only. Since our conception of multiplication is the application of a relation, we can only multiply absolute terms by considering them as relatives.</p> | <p>Thus far, we have considered the multiplication of relative terms only. Since our conception of multiplication is the application of a relation, we can only multiply absolute terms by considering them as relatives.</p> | ||

| − | <p>Now the absolute term | + | <p>Now the absolute term “man” is really exactly equivalent to the relative term “man that is ——”, and so with any other. I shall write a comma after any absolute term to show that it is so regarded as a relative term.</p> |

| − | <p>Then | + | <p>Then “man that is black” will be written:</p> |

|- | |- | ||

| align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m},\!\mathrm{b}</math> | | align="center" | <math>\mathrm{m},\!\mathrm{b}</math> | ||

| Line 1,788: | Line 1,733: | ||

<math>\begin{array}{*{11}{c}} | <math>\begin{array}{*{11}{c}} | ||

\mathrm{m,} | \mathrm{m,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{man that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{man that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

& = & \mathrm{C}:\mathrm{C} | & = & \mathrm{C}:\mathrm{C} | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{I}:\mathrm{I} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{I}:\mathrm{I} | ||

| Line 1,795: | Line 1,740: | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

\mathrm{n,} | \mathrm{n,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{noble that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{noble that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

& = & \mathrm{C}:\mathrm{C} | & = & \mathrm{C}:\mathrm{C} | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{D}:\mathrm{D} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D}:\mathrm{D} | ||

| Line 1,801: | Line 1,746: | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

\mathrm{w,} | \mathrm{w,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{woman that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{woman that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

& = & \mathrm{B}:\mathrm{B} | & = & \mathrm{B}:\mathrm{B} | ||

& +\!\!, & \mathrm{D}:\mathrm{D} | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D}:\mathrm{D} | ||

| Line 1,918: | Line 1,863: | ||

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" <!--QUOTE--> | ||

| | | | ||

| − | <p>Let us then suppose that the universe of our discourse is the actual universe, so that words are to be used in the full extent of their meaning, and let us consider the two mental operations implied by the words | + | <p>Let us then suppose that the universe of our discourse is the actual universe, so that words are to be used in the full extent of their meaning, and let us consider the two mental operations implied by the words “white” and “men”. The word “men” implies the operation of selecting in thought from its subject, the universe, all men; and the resulting conception, ''men'', becomes the subject of the next operation. The operation implied by the word “white” is that of selecting from its subject, “men”, all of that class which are white. The final resulting conception is that of “white men”.</p> |

| − | <p>Now it is perfectly apparent that if the operations above described had been performed in a converse order, the result would have been the same. Whether we begin by forming the conception of | + | <p>Now it is perfectly apparent that if the operations above described had been performed in a converse order, the result would have been the same. Whether we begin by forming the conception of “''men''”, and then by a second intellectual act limit that conception to “white men”, or whether we begin by forming the conception of “white objects”, and then limit it to such of that class as are “men”, is perfectly indifferent so far as the result is concerned. It is obvious that the order of the mental processes would be equally indifferent if for the words “white” and “men” we substituted any other descriptive or appellative terms whatever, provided only that their meaning was fixed and absolute. And thus the indifference of the order of two successive acts of the faculty of Conception, the one of which furnishes the subject upon which the other is supposed to operate, is a general condition of the exercise of that faculty. It is a law of the mind, and it is the real origin of that law of the literal symbols of Logic which constitutes its formal expression (1) Chap. II, [ namely, <math>xy = yx~\!</math> ].</p> |

<p>It is equally clear that the mental operation above described is of such a nature that its effect is not altered by repetition. Suppose that by a definite act of conception the attention has been fixed upon men, and that by another exercise of the same faculty we limit it to those of the race who are white. Then any further repetition of the latter mental act, by which the attention is limited to white objects, does not in any way modify the conception arrived at, viz., that of white men. This is also an example of a general law of the mind, and it has its formal expression in the law ((2) Chap. II) of the literal symbols [ namely, <math>x^2 = x\!</math> ].</p> | <p>It is equally clear that the mental operation above described is of such a nature that its effect is not altered by repetition. Suppose that by a definite act of conception the attention has been fixed upon men, and that by another exercise of the same faculty we limit it to those of the race who are white. Then any further repetition of the latter mental act, by which the attention is limited to white objects, does not in any way modify the conception arrived at, viz., that of white men. This is also an example of a general law of the mind, and it has its formal expression in the law ((2) Chap. II) of the literal symbols [ namely, <math>x^2 = x\!</math> ].</p> | ||

| Line 2,000: | Line 1,945: | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

\mathbf{1,} | \mathbf{1,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{anything that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{anything that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | & = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | ||

\\[9pt] | \\[9pt] | ||

\mathrm{m,} | \mathrm{m,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{man that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{man that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | & = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | ||

\\[9pt] | \\[9pt] | ||

\mathrm{n,} | \mathrm{n,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{noble that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{noble that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | & = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | ||

\\[9pt] | \\[9pt] | ||

\mathrm{w,} | \mathrm{w,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{woman that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{woman that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} | & = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} | ||

| Line 2,054: | Line 1,999: | ||

===Commentary Note 9.5=== | ===Commentary Note 9.5=== | ||

| − | Peirce's comma operation, in its application to an absolute term, is tantamount to the representation of that term's denotation as an idempotent transformation, which is commonly represented as a diagonal matrix. | + | Peirce's comma operation, in its application to an absolute term, is tantamount to the representation of that term's denotation as an idempotent transformation, which is commonly represented as a diagonal matrix. Hence the alternate name, ''diagonal extension''. |

| − | An idempotent element <math>x\!</math> is given by the abstract condition that <math>xx = x,\!</math> but | + | An idempotent element <math>x\!</math> is given by the abstract condition that <math>xx = x,\!</math> but elements like these are commonly encountered in more concrete circumstances, acting as operators or transformations on other sets or spaces, and in that action they will often be represented as matrices of coefficients. |

| − | Let's see how | + | Let's see how this looks in the matrix and graph pictures of absolute and relative terms: |

| − | Absolute | + | ====Absolute Terms==== |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{*{17}{l}} | <math>\begin{array}{*{17}{l}} | ||

| − | \mathbf{1} | + | \mathbf{1} & = & \text{anything} & = & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{B} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{C} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{C} | + | \mathrm{D} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} | + | \mathrm{E} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{E} | + | \mathrm{I} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{I} | + | \mathrm{J} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{J} | + | \mathrm{O} |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{O} | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

| − | \mathrm{m} | + | \mathrm{m} & = & \text{man} & = & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{C} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{I} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{I} | + | \mathrm{J} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{J} | + | \mathrm{O} |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{O} | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

| − | \mathrm{n} | + | \mathrm{n} & = & \text{noble} & = & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{C} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{D} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} | + | \mathrm{O} |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{O} | ||

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

| − | \mathrm{w} | + | \mathrm{w} & = & \text{woman} & = & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{B} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & = | + | \mathrm{D} & +\!\!, & |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{D} | + | \mathrm{E} |

| − | & +\!\!, & \mathrm{E} | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Previously, we represented absolute terms as column | + | Previously, we represented absolute terms as column arrays. The above four terms are given by the columns of the following table: |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| | | | ||

<math>\begin{array}{c|cccc} | <math>\begin{array}{c|cccc} | ||

| − | \text{ } & \mathbf{1} & \mathrm{m} & \mathrm{n} & \mathrm{w} | + | \text{ } & \mathbf{1} & \mathrm{m} & \mathrm{n} & \mathrm{w} \\ |

| − | \\ | + | \text{---} & \text{---} & \text{---} & \text{---} & \text{---} \\ |

| − | \text{---} & \text{---} & \text{---} & \text{---} & \text{---} | + | \mathrm{B} & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | \\ | + | \mathrm{C} & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 \\ |

| − | \mathrm{B} & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 | + | \mathrm{D} & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ |

| − | \\ | + | \mathrm{E} & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ |

| − | \mathrm{C} & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 | + | \mathrm{I} & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | \\ | + | \mathrm{J} & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ |

| − | \mathrm{D} & 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 | ||

| − | \\ | ||

| − | \mathrm{E} & 1 & 0 & 0 & 1 | ||

| − | \\ | ||

| − | \mathrm{I} & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 | ||

| − | \\ | ||

| − | \mathrm{J} & 1 & 1 & 0 & 0 | ||

| − | \\ | ||

\mathrm{O} & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 | \mathrm{O} & 1 & 1 & 1 & 0 | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | One way to | + | The types of graphs known as ''bigraphs'' or ''bipartite graphs'' can be used to picture simple relative terms, dyadic relations, and their corresponding logical matrices. One way to bring absolute terms and their corresponding sets of individuals into the bigraph picture is to mark the nodes in some way, for example, hollow nodes for non-members and filled nodes for members of the indicated set, as shown below: |

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="90%" |

| − | | | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 4.1.jpg]] || (4.1) |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 4.2.jpg]] || (4.2) | |

| − | 1 | + | |- |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 4.3.jpg]] || (4.3) | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 4.4.jpg]] || (4.4) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Diagonal | + | ====Diagonal Extensions==== |

{| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellspacing="6" width="90%" | ||

| Line 2,146: | Line 2,072: | ||

<math>\begin{array}{lll} | <math>\begin{array}{lll} | ||

\mathbf{1,} | \mathbf{1,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{anything that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{anything that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | & = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | ||

\\[9pt] | \\[9pt] | ||

\mathrm{m,} | \mathrm{m,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{man that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{man that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | & = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{I}\!:\!\mathrm{I} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{J}\!:\!\mathrm{J} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | ||

\\[9pt] | \\[9pt] | ||

\mathrm{n,} | \mathrm{n,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{noble that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{noble that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | & = & \mathrm{C}\!:\!\mathrm{C} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{O}\!:\!\mathrm{O} | ||

\\[9pt] | \\[9pt] | ||

\mathrm{w,} | \mathrm{w,} | ||

| − | & = & \text{woman that is}\, \underline{~~~~} | + | & = & \text{woman that is}\, \underline{~~ ~~} |

\\[6pt] | \\[6pt] | ||

& = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} | & = & \mathrm{B}\!:\!\mathrm{B} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{D}\!:\!\mathrm{D} ~+\!\!,~ \mathrm{E}\!:\!\mathrm{E} | ||

| Line 2,325: | Line 2,251: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | Cast into the bigraph picture of | + | Cast into the bigraph picture of dyadic relations, the diagonal extension of an absolute term takes on a very distinctive sort of “straight-laced” character: |

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="90%" |

| − | | | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 5.1.jpg]] || (5.1) |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 5.2.jpg]] || (5.2) | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 5.3.jpg]] || (5.3) | |

| − | + | |- | |

| − | + | | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 5.4.jpg]] || (5.4) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| − | + | ===Commentary Note 9.6=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Just to be doggedly persistent about it, here is what ought to be a sufficient sample of products involving the multiplication of a comma relative onto an absolute term, presented in both matrix and bigraph pictures. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Example 1==== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ====Example 1==== | ||

{| align="center" cellpadding="6" width="90%" | {| align="center" cellpadding="6" width="90%" | ||

| − | | <math>\mathbf{1,}\mathbf{1} ~=~ \mathbf{1}</math> | + | | <math>\mathbf{1,}\mathbf{1} ~=~ \mathbf{1}\!</math> |

|- | |- | ||

| <math>\text{anything that is anything} ~=~ \text{anything}</math> | | <math>\text{anything that is anything} ~=~ \text{anything}</math> | ||

| Line 2,417: | Line 2,301: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="100%" |

| − | | | + | | width="2%" | |

| − | + | | width="48%" | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 6.1.jpg]] | |

| − | + | | width="50%" | (6.1) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,466: | Line 2,341: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="100%" |

| − | | | + | | width="2%" | |

| − | + | | width="48%" | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 6.2.jpg]] | |

| − | + | | width="50%" | (6.2) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | | | ||

| − | | | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,515: | Line 2,381: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="100%" |

| − | | | + | | width="2%" | |

| − | + | | width="48%" | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 6.3.jpg]] | |

| − | + | | width="50%" | (6.3) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,562: | Line 2,419: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="100%" |

| − | | | + | | width="2%" | |

| − | + | | width="48%" | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 6.4.jpg]] | |

| − | + | | width="50%" | (6.4) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,609: | Line 2,457: | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | {| align="center" | + | {| align="center" cellpadding="10" width="100%" |

| − | | | + | | width="2%" | |

| − | + | | width="48%" | [[Image:LOR 1870 Figure 6.5.jpg]] | |

| − | + | | width="50%" | (6.5) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

|} | |} | ||

| Line 2,628: | Line 2,467: | ||